The Amenities Wars and the Problem with the Lens of the National “Student Market”

A presentation to UA's "Open the Books Symposium," Feb. 1, 2018, by Prof. Beth Mintz

I would like to start with a very brief overview of why college is so expensive. First and foremost, higher ed is extremely labor intensive: we’re highly educated and highly paid. And this includes administrators, managers, and non-teaching professionals and there are a lot of us. In addition, although in many sectors, technology is replacing people, this is not happening at the university. Technology does not replace large numbers of individuals, but instead it adds another level of relatively expensive employees. So when the university says that an enormous part of their budget goes to salaries, it’s true.

But there are other things going on as well, of course. For public institutions, just about every state in the union has decreased the amount of money that they give to higher education and the only solution that universities have found to make up the lost funding is to increase tuition. So to the extent that states defund or decrease their contributions to their state institutions, students make up the difference. This is pretty well understood, at least in the literature.

What I’d like to concentrate on here is another component, one that is less well known, and that is marketization. Here is a formal definition: marketization is the increasing influence of competition and market logic on cost structures. And in the context of the university, it most importantly takes the form of schools competing with each other for students and student dollars.

Surprisingly, at least for somebody who has been in the academic world for a long time, the “market” has become a part of the lexicon on the academy. The Chronicle of Higher Education, for example, writes that, “to succeed, colleges need to use modern marketing tools to reach prospective students and invest in staff on the ground to work with high schools and in college fairs” (2017, p. 5). We used to talk about academic mission, or intellectual ideas, or the life of the mind. Now, in many contexts, we talk about the market and the need to market. And this, I suggest, is a fundamental change.

The market: when did it happen, how did it happen? It has been a long time coming, without doubt, but one of the signals or one of the defining moments in the development of the university as a market, came with the beginning of what some call the “amenities wars.” The above quote -- note the date at the bottom, “1999.” -- describes something that was new at the time: the introduction of the super dorm. What is so interesting about it, and why it is so important, is the dynamic that this initiated. That is: BU introduced the upscale dorm and this gave them a competitive advantage, at least temporarily. However, it didn’t take very long for other campuses to notice that advantage and to try the same thing. And before we knew it, campuses throughout the country were upgrading their dormitories and their other facilities. So the dynamic: once everybody upped their game, the initial competitive advantage was lost, while the costs remain.

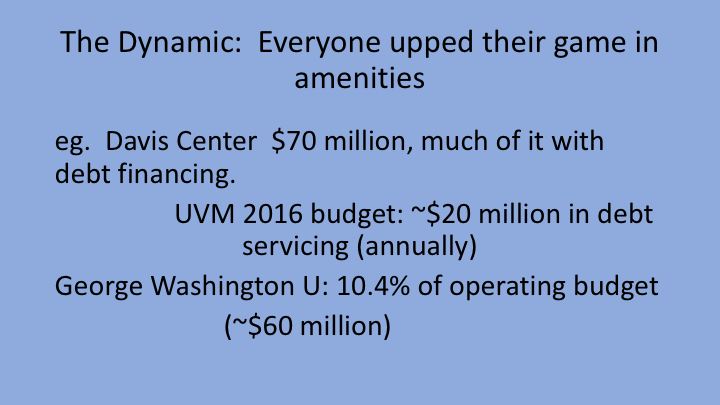

We see the same dynamic with student unions. Here on campus, the Davis Center cost about $70 million -- and as an aside, note $70 million plus day-to-day maintenance and upkeep. Although financed by a very generous gift from the Davis family, a good chunk of cost was borrowed, with a repayment schedule that includes yearly interest payments. If you look at a recent UVM budget, you can see that we spent about $20 million in debt servicing and that $20 million is a recurring item, payable every single year. But when more and more schools have attractive student centers, there is no competitive advantage; rather it becomes a very expensive necessity. With another large investment in an athletic complex in our future, debt-servicing costs are going to continue to rise.

It is not only UVM and that is the problem. Many, many colleges and universities are doing the same thing. Consider George Washington University, for example. They spend 10.4% of their operating budget annually on debt financing, or about $60 million a year. Imagine how many faculty that could buy.

We see the same dynamic in Student Services. When one institution innovates and introduces another service, innovation travels and once everyone has them, there is no competitive advantage. This money isn’t wasted; the services are real, but they can be very, very expensive. Here at UVM, about 8.4% of spending is on student services, but that is an extremely narrow definition. Using a broader definition and it comes to about 28% of the operating budget.

Importantly, growth in student services explains a good part of the growth of administrators and non-teaching professionals on campuses nationally, including the University of Vermont. And note that that the increase in these groups has vastly out-paced the growth in students and faculty.

I assume that everybody with any experience with higher ed knows about the U.S. News & World Report rankings. And I imagine that everyone know that those rankings are taken very seriously by college administrators, since schools compete for rankings in order to recruit students.

The importance of SAT scores to an institution’s ranking has led to a practice that is called tuition discounting, another thing that began as a mechanism for competitive advantage. The idea is to use merit scholarships to recruit high-achieving students, who will have an impact on an institution’s U.S. News & World Report rankings, making it more attractive to students, in general. Well, it really worked. Early innovators offered extra money to strong students and they came. As you can imagine, it is the same dynamic as the amenities “wars”: once other schools caught on, tuition discounting became very common. Indeed, if there is one financial killer in higher ed today, it’s this idea of tuition discounting. Almost everybody is doing it and nobody can back off. Two-thirds of students in public institutions receive merit money, while 80% of students in private institutions do so.

The latest data I found easily for UVM was 2014. Look at the above slide carefully: $84 million. Yes. $84 million. It’s an enormous sum. And that’s 26% of the general pie, all in this dynamic where one innovates and the rest of us just follow suit and try catch up. Importantly, merit money usually comes at the expense of need-based scholarships. I couldn’t find data for UVM on this, but only 38% of financial aid in public universities and colleges in the United States is need based. That means 62 percent goes toward merit, and since SAT scores are highly correlated with family income, merit money tends to go to upper income kids.

Honors colleges are another example. They are not a huge expense, but the process is the same: one set of institutions innovated in order to boost recruitment of high achievers. Now we all have them, with any type of competitive advantage long gone and no hope of getting rid of them if we so chose.

So in sum, then, why is UVM so expensive? Lots of reasons. First, higher ed is highly labor intensive, but lack of reasonable state funding leaves us particularly vulnerable. Here I have considered the role of marketization. We do what other schools do and have gotten immersed in a cycle that is unending and expensive.

An alternative vision for UVM: in the short-term, step away from the amenities arms race, and instead invest in academic quality, including valuing our faculty. And invest in a niche, something that we have unique quality and unique resources to do.

In the longer term, redefine education as a public good, something that will “raise all ships.” This would go hand in hand with free tuition, something that would increase national educational attainment while also contributing to equality. And in reference to the marketization of higher education, free tuition would exert downward, rather than upward, cost pressure.